When it comes to architecture, do the ends justify the means or is it the other way around? What exactly is the relationship between process and product? Is process even relevant in and of itself, or does only the final structure carry meaning?

Does it matter how the chocolate cake was made, or just how it tastes?

For some architects, process has its own value. Obviously, every building is designed through a process—none of them just spontaneously appear as complete entities (although, we’ll address parametrics later). Process fulfills an important role within architecture—that is undeniable. What I really want to address is the notion that the decision process in and of itself can be used to justify the final design instead of the merits of the complete solution being what provides justification for architecture. While each design process is certainly beneficial for the architect’s own development, I believe the final building—the building, not just the presented design and drawings—can really be the only basis upon which its success can be judged.

There are certainly architects, really good ones, who place the majority of importance upon their creative process. They use their own path of reasoning to explain to the public and their clients why we should buy into their version of reality. They posture that the building isn’t just about the present experience of standing in or moving through it, but that the building is about its present existence and its creation history. They argue that buildings don’t create meaning on their own, but on their connections with external factors.

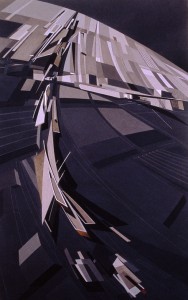

Sometimes this emphasis is called site mapping, which is when an architect explains their design decisions as tangible links to the landscape or human context surrounding the site. From this viewpoint, the final design is presented as inevitable. As my professor, David Heymann, puts it: the architect is just the mid-wife. In other words, architects using site-mapping are essentially saying that they didn’t birth the design, they merely pulled it forth from site. (There is false humility lurking there, but let’s accept this premise for now.) Two well-known examples of this are Zaha Hadid’s Vitra Fire Station in Italy, and Daniel Libeskind’s Holocaust Museum in Berlin, Germany.

These two buildings wear their site-mapping process loudly and proudly. About his Holocaust Museum in Berlin, Libeskind (“Jewish Museum”, 1989) explains:

“… I felt that the physical trace of Berlin was not the only trace, but rather that there was an invisible matrix or anamnesis of connections in relationship. I found this connection between figures of Germans and Jews. I felt that certain people and particularly certain writers, composers, artists and poets formed the link between Jewish tradition and German culture. So I found this connection and I plotted an irrational matrix which was in the form of a system of intertwining triangles which would yield some reference to the emblematics of a compressed and distorted star: the yellow star that was so frequently worn on this very site.”

This is an interesting conceptual connection, but does the average visitor understand it? Are they aware of it? Perhaps they’re oblivious of the specific ties, but it’s also possible that this larger framework creates an experience that is impactful—exactly what Libeskind intended. It’s this experience that measures the success of the building. The ability of the building to shape its visitors’ experiences in a particular way is the way we should judge designs to be great or abysmal. Process is salutary insofar as it creates an intended environment. Once it has done so, it has done its piece and is no longer needed to validate a design. Process is valuable to understand because of how it explains how spatial experiences are manipulated. Yet in the end, experience is the only way to validate a structure.

This leads me to a tangent about the role of parametric design within architecture. Parametric design, or a design process using a set of parameters (as the name dictates) is less about a conceptual development of the architectural idea and centralizes upon the use of algorithms to create ideal designs based upon a number of factors.

Parametric design can be interpreted in two opposite ways. It means either that the process itself is the most and really the only important part of the design and that the building is secondary or unimportant except as the output of a number variables. Likewise, it can also be interpreted as the fact that the process is completely without value and unimportant and only the building itself has any value as a complete solution to a particular set of variables. So either it is completely process-important and design-irrelevant or ostensibly process-unimportant and design-triumphant. Which is it?

This is a difficult question to answer. I believe that the current atmosphere within the profession would mostly say that, at this moment, parametric design is relevant as a new creative process. However, I suspect that this will change in a number of years. I believe that ultimately, parametric design is a non-process process. Right now its novelty is making it appear as though it is a process simply because the algorithms haven’t been perfected or standardized in any sort of way. To put it another way, creating the parametric algorithms IS the creative design process at the moment. Once the wrinkles are ironed out, parametric design effectively removes creativity from the equation (I couldn’t help the pun) and produces complex and complete building design without the intervention of an architect.

If you’ll allow me to proceed down the rabbit hole of a tangent from a tangent, I’d like to pose the question now about the role of an architect in parametric design. If parametrics are devoid of creativity and are essentially the domain of an engineer, computer or structural, do architects have a place within this future?

To be honest, no, I don’t believe parametric design will be the death of the architecture field. I do believe it will replace some architectural design, but probably not in any way that we, as architects, will be upset about losing. There’s already a great deal of poor architecture being built, and parametrics may or may not fall into that field—it will probably depend upon the building in any case. I would be willing to bet that we may find parametrics useful as a starting point for some buildings. I can see it being incredibly useful in hospital design, which is so complex and has to be so tightly controlled, that the benefits of having a computer work out many of the difficulties in order for an architect to then add the human touches afterwards and in areas where they can be effective is an enticing idea. In fact, as a tool, it can be an incredibly useful device. Left on its own, it will probably have a few hits but mostly misses.

I believe that when the novelty wears off, it will probably be put in the bin with CAD and BIM as a tool and a means rather than an ends.

If you go to Bjarke Ingels Group’s (BIG) website, [big.dk] you see drawings for each of their projects [big.dk/projects/8/] explaining how they reached their final design. They aren’t necessarily site mapping, but they show the progression of the design from an indescript rectangle to the final complicated and impressive scheme. The little diagrams are helpful for understanding how a building functions or responds to its surroundings.

In fact, these little diagrams are frequently my favorite parts of the drawings because they help me best understand how the building works. I’m mostly interested in these as a design and architecture student. They explain how the design came to be and give me ideas for future projects. As a graphic designer in my previous life, I have to say that BIG does a wonderful job of illustrating ideas in a clear way, and I try to learn from that as well.

These processes are just as valid as any other design process, I’m not denying their usefulness. My question is, however: how can you fairly judge a space that you haven’t experienced? No.

Could you really judge how good a chocolate cake is just by reading a recipe? Wouldn’t you want to taste it? Isn’t it possible that even if the ingredients look right, and the amounts look right, that it could still taste a little… funny? Or bland? Or dry?

By all means, bakers should have fun in the kitchen, but I rather eat delicious cake.